Publication of “Kyoto Area Studies on Asia”

"Money-lending Contracts in Konbaung Burma: The Importance of Local Documents in Interpreting Early Modern Society in Southeast Asia"

R4 3-1(R4 AY2022)

| Project Leader | Saito Teruko(Tokyo University of Foreign Studies) |

| Research Project | Money-lending Contracts in Konbaung Burma: The Importance of Local Documents in Interpreting Early Modern Society in Southeast Asia |

| Countries of Study | Myanmar |

Contents of Publication

This study demonstrates the potential of local documents to research on early modern Southeast Asia, a field that has been largely unexplored until now. The study was made possible by the discovery of a large number of debt contracts that were popular among common people in 18th and 19th century Burma. By analyzing these contracts, the author was able to trace socioeconomic changes and their historical significance in early modern Burma. Furthermore, by examining how contracts exchanged by private individuals were honored in a context where the intervention of public authorities was rare, she has shed light on the nature of early modern Burmese society.

Purpose of Research, Its Significance and Expected Results, etc.

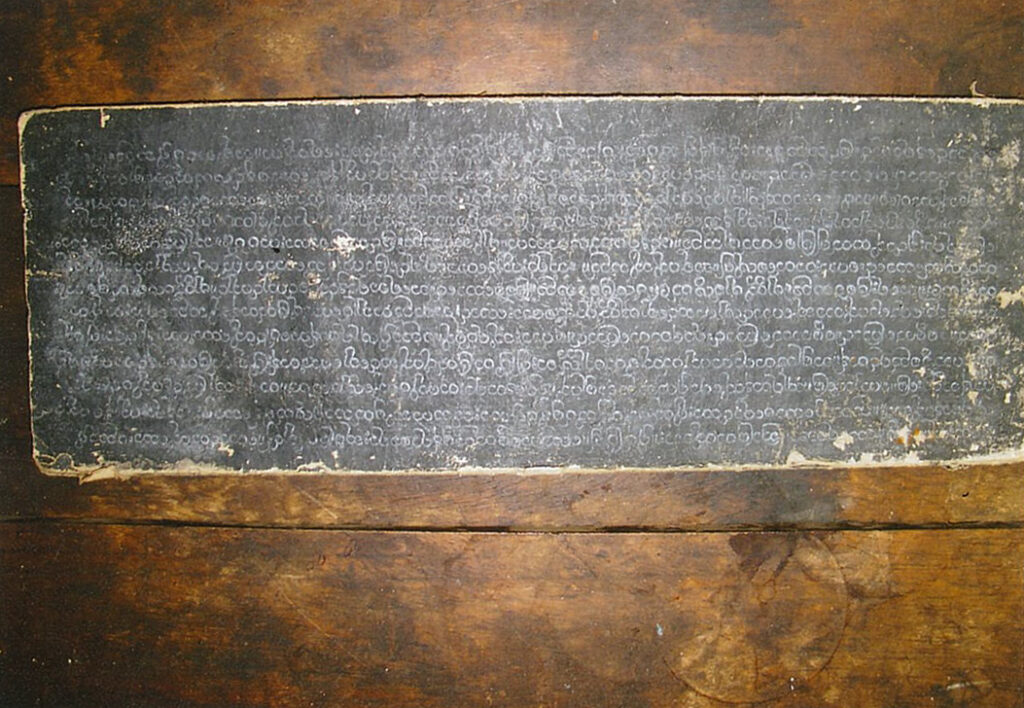

Except for Vietnam, the premodern history of Southeast Asian countries has been drawn primarily from records taken by outsiders, apart from royal chronicles, customary codes, and local literary works. Scholars have often assumed that no local records remained of the daily lives of ordinary people. However, the abundant records of the daily lives of people in 18th and 19th century Burma, in the form traditional folded manuscripts called para-baik, seems to indicate that similar materials may exist in other Southeast Asian countries. The primary objective of the author is that the publication of this research will stimulate the pursuit and research of local materials in other regions.

The life of Burma’s para-baik records is nearly exhausted. Thanks to the efforts of librarians and archivists who have been collecting and preserving these materials since the late 1980s, many have been preserved for up to 200-250 years, but even so, less than half of the materials that remain are fully legible. The number of people who carefully read and study these materials is also extremely small.

By demonstrating that the information contained in these materials helps us greatly to understand the nature of the society as well as the daily lives of common people whose names have never appeared in the early modern history of the region, the author hopes that young researchers and librarians will actively take part in the study of these manuscripts. By writing in English, she hopes that the publication will reach a wide audience of researchers and scholars of the region and beyond.

During the 18th and first half of the 19th century, various types of land came into the hands of influential families through loans. This shook the very foundations of the land system of the day.

The irrigation networks built during the 11th century made the region one of the largest granaries in the kingdom. The manuscripts well-preserved by the ruling families in Salin are valuable historical documents.

Para-baiks were easily damaged by water, insects, and mold. As they were written with soft white stone pencils, the written characters often fade away due to friction.